Secure Land Rights for Climate Resilience

The world’s attention this week has turned to Katowice, Poland, where leaders and advocates have gathered to discuss the global climate change agenda at the COP24 United Nations Climate Change convening. Coming on the heels of the grim report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), there is a profound sense of urgency not only to take more drastic measures to mitigate climate change, but also to bolster efforts to support the adaptive capacity of those most affected.

Worldwide, the consequences of climate change are increasingly evident, and the link to land rights is increasingly hard to ignore.

In Central America, a “hungry caravan” of migrants have left their homes, seeking relief from a protracted drought that has consumed food crops and contributed to widespread poverty.

In India, more than half of the country is under high levels of water stress, leaving a staggering 600 million people at increased risk of experiencing water shortages.

And in the Horn of Africa, the New York Times reports that more than 650,000 children under age 5 are severely malnourished, the consequence of a series of droughts that have “pushed millions of the world’s poorest to the edge of survival.”

These examples are stark reminders that the most severe consequences of climate change are being inflicted upon people living in the Global South, many of whom base their livelihoods on the ability to access, use, and cultivate land.

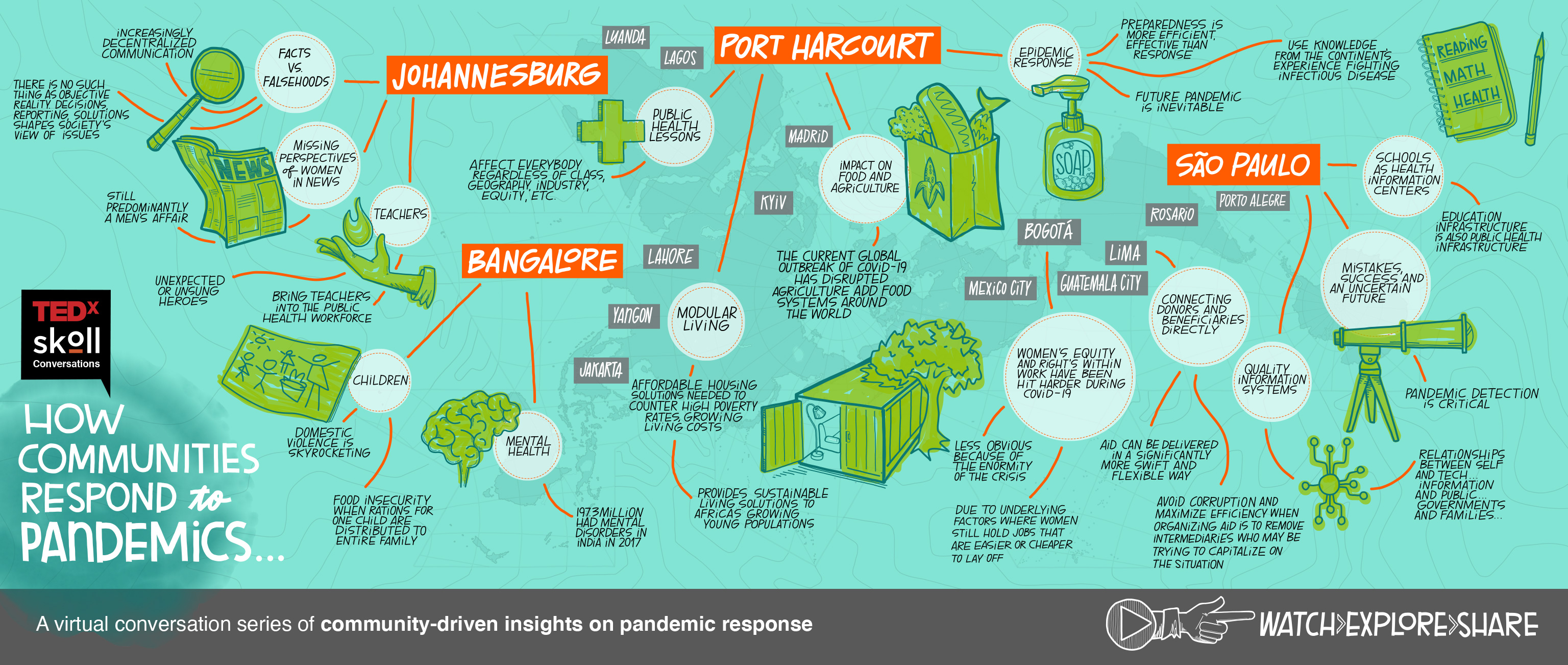

We’ve written previously about how land rights can promote food security and climate resilience among rural women, men, and communities. A new Landesa infographic captures the climate-related drivers of food insecurity in the Global South, and how land rights encourage the types of investments that can make farmers more resilient.

Every person on earth is affected by climate change in some form, but people in the world’s poorest places tend to bear the brunt of its consequences. This is in part because the majority of the world’s poorest live in the Global South, where scant resources and inadequate infrastructure leave countries ill-equipped to adapt to a changing climate.

What’s more, many millions live in rural areas and rely on land (and agriculture) for their livelihoods, making them more susceptible to extreme temperatures and drought that deplete soils and devastate crops. According to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), an estimated 1.5 billion people worldwide – about one-fifth of the world’s population – are directly affected by land degradation.

The UNCCD also estimates that more frequent drought will leave 1.8 billion people experiencing absolute water scarcity by 2025 – dire circumstances for rural farmers, many of whom rely on rain-fed agriculture to grow food. Yields from such rain-fed farms could fall by 22 percent across sub-Saharan Africa and as much as 50 percent in some countries within the next two years.

With approximately 820 million people worldwide already chronically undernourished and climate-related pressures on food security increasing, such trends are deeply troubling for a global community that has committed to Zero Hunger.

Complex problems defy simply solutions, and it will take a multifaceted approach to address the growing crisis over climate-induced food insecurity. But secure land rights for rural women, men, and communities are a critical piece of the puzzle.

Sustainable agriculture and land management practices — such as improved irrigation, terracing, fallowing, and agroforestry — are widely understood to conserve soil and water, building climate resiliency and boosting agricultural productivity, in both the short- and long-term.

But they’re not free. Such investments require time, labor, and often money. Without secure land rights, rural landholders often lack both the resources and confidence to make critical investments to improve their land and adapt to a changing climate.

On the other hand, farmers with secure land rights are often more inclined and equipped to make climate-smart investments, including soil conservation and planting (and preserving) trees.

What is needed to equip rural women and men with secure rights to the land they farm? One route could be through the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which includes a mechanism for member states to make commitments for taking action on climate change.

Each of the 184 parties that have ratified the Paris Agreement – the UN’s landmark agreement to combat climate change – committed to producing national climate action plans, referred to as “Nationally Determined Contributions,” or NDCs. These NDCs map out each country’s strategy for fulfilling national commitments codified in the Paris Agreement. Yet only a handful of NDCs mention land rights or tenure security as a key intervention for building climate resiliency and adaptation.

This is a missed opportunity. As world leaders, climate scientists, researchers, and members of civil society debate the global climate change agenda, their efforts must account for the billions of rural people who bear little responsibility for causing climate change but are most vulnerable to its consequences. Land rights are an important way to confront this immense inequality and promote a more secure world for all.

Image: Debbie Espinoza